By Hugh Malkin - lifelong swimmer, father to two children at Virginia Highland Elementary, and avid bicycle commuter

Summary: Atlanta faces a severe "aquatic deficit": unlike its suburbs, our city's dense neighborhoods, especially around the Beltline, have almost no public summer swim teams. This isn't just about fun; it's a safety crisis, as drowning is a leading cause of death for children. Specifically, the Midtown High School district lacks a public pool capable of hosting a swim team. A recent community effort to build one in Virginia-Highland unfortunately failed due to procedural hurdles and neighborhood opposition. To fix this, we're calling on the City of Atlanta Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR) and Atlanta Public Schools (APS) to work together immediately to create a city-wide public summer swim league and build a new facility for the Midtown High School district. This is crucial for equipping our children with life-saving swimming skills and building stronger communities.

Neighborhood summer swim teams are more than just a summer pastime; they're crucial for teaching children life-saving swimming skills, promoting physical activity, and strengthening community bonds. However, the City of Atlanta faces a significant challenge: an "aquatic deficit." While its suburbs are dotted with numerous swim teams, the 45 neighborhoods within and around the Atlanta Beltline, one of the state's most densely populated areas, have only one public summer swim team. This isn't just an inconvenience; it's a serious safety issue, especially since drowning remains a leading cause of death for children.

As a lifelong swimmer and a parent, I've personally experienced the frustration of this shortage, watching my own children navigate summers without easy access to public swim teams.

A Look Back: The Disappearance of Atlanta's Pools

To understand Atlanta's current aquatic shortfall, we need to examine its past. Hannah Palmer, in her book and art installation Ghost Pools: A brief history of swimming in Atlanta and across America, uncovered a forgotten legacy. Atlanta was once known as "the swimmingest city in the country," boasting numerous public pools that were thoroughly enjoyed by its residents.

However, this legacy unraveled starting in the 1950s. Palmer's research reveals that as pools began to desegregate, many white swimmers abandoned them. This shift led to a decline in the city's commitment, a drying up of funding, and the eventual closure or disrepair of public pools, leaving many neighborhoods with what can now be called "aquatic deserts."

This historical context has a measurable impact today, especially when it comes to swimming proficiency among different racial groups. National studies show significant disparities: 64% of Black children, 45% of Hispanic/Latino children, and 40% of White children have low to no swimming skills. These statistics highlight a critical safety concern, placing these groups at a much higher risk of drowning. Palmer's "Ghost Pools" installations, which use light and sound to create mock pools where real ones once stood, serve as stark reminders of this lost public infrastructure.

Ghost Pools. Commissioned by Flux Projects with the City of East Point Julie Yarbrough Photography

The Current Landscape and a Proposed Solution

This history casts a long shadow. The aquatic deficit has left Atlanta Public Schools (APS) and the City of Atlanta falling short in adequately meeting community aquatic needs. Opportunities for water safety education and team swimming are glaringly absent in many of Atlanta's densest urban areas. Critically, no public summer swim teams operate near the Atlanta Beltline, one of the state’s most densely populated and fastest-growing urban corridors.

Map of Atlanta’s public swim teams

An ideal solution involves the City of Atlanta's Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR) collaborating with Atlanta Public Schools (APS) to establish a summer swim team league. Both organizations share a commitment to equity and community well-being. DPR's "Activate ATL" plan, adopted in December 2021, aims to improve infrastructure and expand offerings, with a focus on addressing disparities in "historically underserved parks." Similarly, APS Athletics emphasizes equity and inclusivity, striving to ensure all students have equal access to sports opportunities. This shared vision provides a strong foundation for a collaborative effort.

For a neighborhood swim team, an 8-lane, 25-yard pool is the optimal facility. This size is the official standard for high school and summer league competitions in the U.S., allowing for official meets. Eight lanes, rather than the minimum of six, enable more efficient competitions and better management of practice groups for various ages and skill levels. For safety, the pool should have a minimum depth of four feet at the starting end, though six to seven feet is highly recommended for modern facilities to ensure safety during racing dives. To maximize utility, an "L-shape" design with an attached shallow area provides a dedicated, safe space for younger swimmers and community lessons, making the facility valuable for both competitive training and recreational use.

Currently, most Atlanta High Schools have access to a district pool large enough for a swim team, with the notable exception of Midtown High School. For instance:

Carver: Pittman Park Pool

Douglass: Mozley Park Pool

Maynard Jackson: Grant Park Pool

Mays: CT Martin Pool

North Atlanta: Garden Hills Pool

South Atlanta: Rosel Fann Pool

Therrell: Adams Park Pool

Washington: Washington Park Natatorium

Midtown: The Midtown high school district currently lacks a city pool large enough for a swim team.

Atlanta’s public pools capable of hosting swim teams

A Recent Setback: The Virginia-Highland Pool Project

Recognizing this critical void, proactive parents from Virginia-Highland Elementary (VHE) formed a non-profit, the Virginia-Highland Pool Association (VHPA), to pursue a solution. John Closs, Executive Director of the VHPA and a lifelong swimmer, began working on a proposal in early 2023. They identified an underutilized APS field across from VHE as a potential site for a year-round community pool. The vision was to create a facility that would teach essential swimming skills to APS students and host a much-needed neighborhood summer swim team. Placing the pool on APS property offered a unique opportunity to repurpose high-value, unused land for a community benefit and integrate water safety education into school programs.

Field of Dreams, site of the proposed pool Ponce De Leon Pl NE and Virginia Ave NE, Atlanta, GA 30306 Photo Credit: Abby Closs

After extensive discussions with APS and unanimous support from the Virginia-Highland Civic Association (VHCA) last October, VHPA and APS drafted a pre-development agreement. For VHPA, this was the first step in a multi-year process involving significant fundraising, detailed design, complex permitting, and extensive community engagement. However, VHCA viewed this stage as their last formal opportunity for input.

On April 29, 2025, VHCA presented the project's progress to the community at a town hall. What followed highlighted a common urban planning challenge. A pastor from a nearby church expressed opposition, citing concerns that the pool would create too much demand for street parking, forcing his congregation to park further away. This sentiment was quickly echoed by several long-term residents, who also cited parking as their primary objection. The promising pool proposal suddenly became contentious, reminiscent of other polarizing development debates. While these vocal parking concerns dominated the town hall and online conversations, it's important to note that the VHCA board's ultimate decision was based on a commitment to fair procedure and thorough project vetting, not solely on parking complaints.

VHCA community meeting Tuesday, April 29, 2025

This scenario, where a community might forgo a vital public good like a pool offering life-saving education due to perceived parking scarcity, is precisely what the late UCLA urban planning professor Donald Shoup warned about in his book, The High Cost of Free Parking. Shoup argued that debates over "free" parking often derail higher-value public projects. In this case, a swim team for children was ultimately stalled due to concerns about street parking for cars.

Shoup contended that the perceived individual benefit of free, unregulated on-street parking often leads communities to sacrifice far greater collective benefits, exemplifying a "tragedy of the commons." Such "free" parking, he argued, carries immense hidden costs, including directly obstructing beneficial community projects and encouraging development that isn't conducive to density. While solutions like pricing parking to manage demand exist, the fundamental question remains: what is the true cost of "free" parking when it denies a vital community resource?

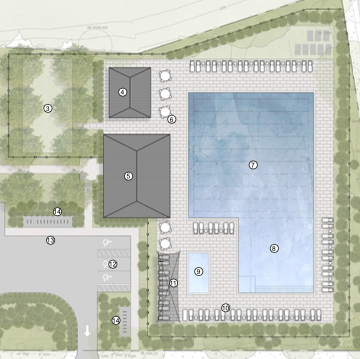

Potential proposal Virginia highland pool site plan

The Project's Demise: Still No Beltline Swim Teams

The community pool project has been shelved for now. Atlanta Public Schools (APS) formally ended the proposal on May 28, 2025, following the VHCA’s unanimous non-support on May 12th. APS had already worked through ten versions of the agreement with VHPA. Despite the option to continue the lengthy dialogue and work through outstanding issues, APS chose to close the door on the project. This decision was likely influenced by multiple factors: vocal neighbor concerns regarding parking (which signaled a potentially difficult process), the VHCA's formal unanimous non-support of this version of the pre-development agreement, and a consideration of locking up their land for a potential 16-year lease versus maintaining the ability to sell it.

The project ultimately fell into a classic procedural "chicken-or-the-egg" trap. The VHCA, a volunteer organization, viewed this specific moment as their only guaranteed opportunity for community input due to APS's zoning exemption. Therefore, they expected detailed architectural plans, traffic studies, and financial assurances upfront—due diligence that is impossible for an all-volunteer nonprofit to produce without initial seed money. Conversely, the VHPA needed the signed pre-development agreement precisely to be able to fundraise for and create those very plans. This stalemate, coupled with the VHCA’s honest effort to treat every proposal equally, meant the VHCA was effectively treating the VHPA as a seasoned developer rather than a non-profit requiring additional guidance. The VHCA communicated its non-support directly to APS, prompting APS to end the proposal before crucial details could be created. Because VHPA would need to raise the pool’s construction funds from the community, the design and its use would inherently need to meet the majority of community needs; the free market would protect the community from an undesirable project by simply not funding it.

In his new book Abundance, Ezra Klein argues that the biggest obstacles to building the infrastructure we need aren’t technological or financial, they’re often legal and procedural. The failure of this specific project serves as a poignant local example. Ultimately, this passionately championed vision succumbed to the impact of a vocal minority and the procedural hurdles that acted as local 'red tape'. Consequently, Virginia-Highland and the wider Beltline communities will continue to lack public pools capable of hosting swim teams. The unfulfilled need and the lessons from this ambitious attempt persist, serving as a testament that while the groundwork was laid, the true cost of these collective hurdles remains evident. If we want more public goods—more pools, parks, and transit—we'll need more than good ideas. We'll need courage to challenge the status quo. And that starts with asking: what are we really protecting when we say no?

A Path Forward: Recommendations for Future Projects

If Atlanta is to build the public amenities its communities deserve, the approval process itself must be reformed. This requires a collaborative approach with specific roles for our city's institutions. The City of Atlanta Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR) and Atlanta Public Schools (APS) Athletics are well-positioned for such collaboration, as their missions and strategic goals significantly overlap. Both prioritize equity, youth development, community engagement, facility optimization, and safety.

Based on the lessons from this experience, here is a framework for how future projects can avoid a similar fate:

Establish a "Public Benefit" Fast Track: The VHCA, NPU-F, and most importantly, the City of Atlanta should create a streamlined approval process specifically for non-profit, public-benefit projects. This would differentiate a volunteer group trying to provide an amenity from a for-profit developer, freeing them from the most onerous requirements designed for large-scale commercial development.

Solve the "Chicken-or-the-Egg" Problem: Atlanta Public Schools (APS) owns significant land in Atlanta, including school properties, vacant lots, and other parcels, some identified for potential redevelopment. These properties are often in highly desirable areas. If Atlantans want to see these properties used for more communal purposes, APS must have a predefined process for partnerships with nonprofits. This could involve providing seed grants or technical assistance before a formal agreement is signed, allowing a volunteer group to produce the preliminary plans that an approving body needs to see. This breaks the stalemate where money can't be raised without an agreement, and an agreement can't be reached without costly plans. The APS Athletics department's emphasis on stakeholder engagement and proposed committees for areas like "Facilities" and "Funding" indicates a readiness for structured collaboration, which could facilitate such arrangements.

Set Clear Decision-Making Criteria: An approving body like the VHCA or APS should be bound by a clear, publicly stated rubric for what constitutes a successful proposal. This shifts the debate from subjective complaints to objective questions. This prevents a solvable issue like parking from derailing a project providing a life-saving public good. A detailed model for such a rubric can be found here.

Develop "Off-the-Shelf" Plans: Why should a volunteer group have to invent a community pool project from scratch? The City of Atlanta's Department of Parks and Recreation should have pre-designed, pre-vetted plans for community pools and other amenities. A group like the VHPA could then propose implementing a version of a city-approved plan, dramatically lowering the barrier to entry. Parks and Rec should work with MARTA and APS—both significant Atlanta landowners—to identify pre-approved sites to address Atlanta’s swim team desert. With daily practices, this would be a huge boon to MARTA ridership, especially if a pool is strategically placed along a bus route in each of Atlanta’s four quadrants. These four pools could form the foundation of a true city-wide championship for the Atlanta Swim Association. DPR's "Activate ATL" plan already focuses on investing in existing assets and connecting resources.

Create a Public Project Accelerator: This fragmentation of city services is precisely the problem this recommendation seeks to solve. There is no single "front door" for a volunteer group like the VHPA to get coordinated guidance, technical assistance, and support to launch a public benefit project. Instead of leaving a volunteer group to navigate this bureaucracy alone, a city agency should act as a partner and guide. This "accelerator" would provide the legal, architectural, and fundraising expertise needed to get public-interest projects off the ground, treating nonprofits as partners in building public abundance. DPR's mission explicitly includes "collaboration," and APS Athletics emphasizes "collaboration and input from various departments," demonstrating a foundational willingness for such a unified approach.

The failure of the Virginia-Highland pool project highlights a critical issue: Atlanta's severe aquatic deficit and our city's difficulty in providing essential public resources. Drowning remains a leading cause of death for children, and the glaring absence of accessible swim facilities, especially near the dense Beltline corridor, is a significant safety crisis that demands immediate action.

We've seen how bureaucratic obstacles and vocal opposition can hinder progress, but we also recognize a clear path forward. It's time for the City of Atlanta Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR) and Atlanta Public Schools (APS) to act on their shared commitment to equity and community well-being.

We specifically call on DPR and APS to collaborate immediately to establish a public summer swim league comparable to those in the suburbs. Furthermore, they must identify a suitable site within the Midtown high school district and construct a pool capable of hosting a summer swim team. This crucial investment will provide a life-saving outlet for our children aged 5 to 18, benefiting them today and for generations to come. This isn't merely about recreation; it's about public safety and fostering a more resilient and equitable Atlanta.